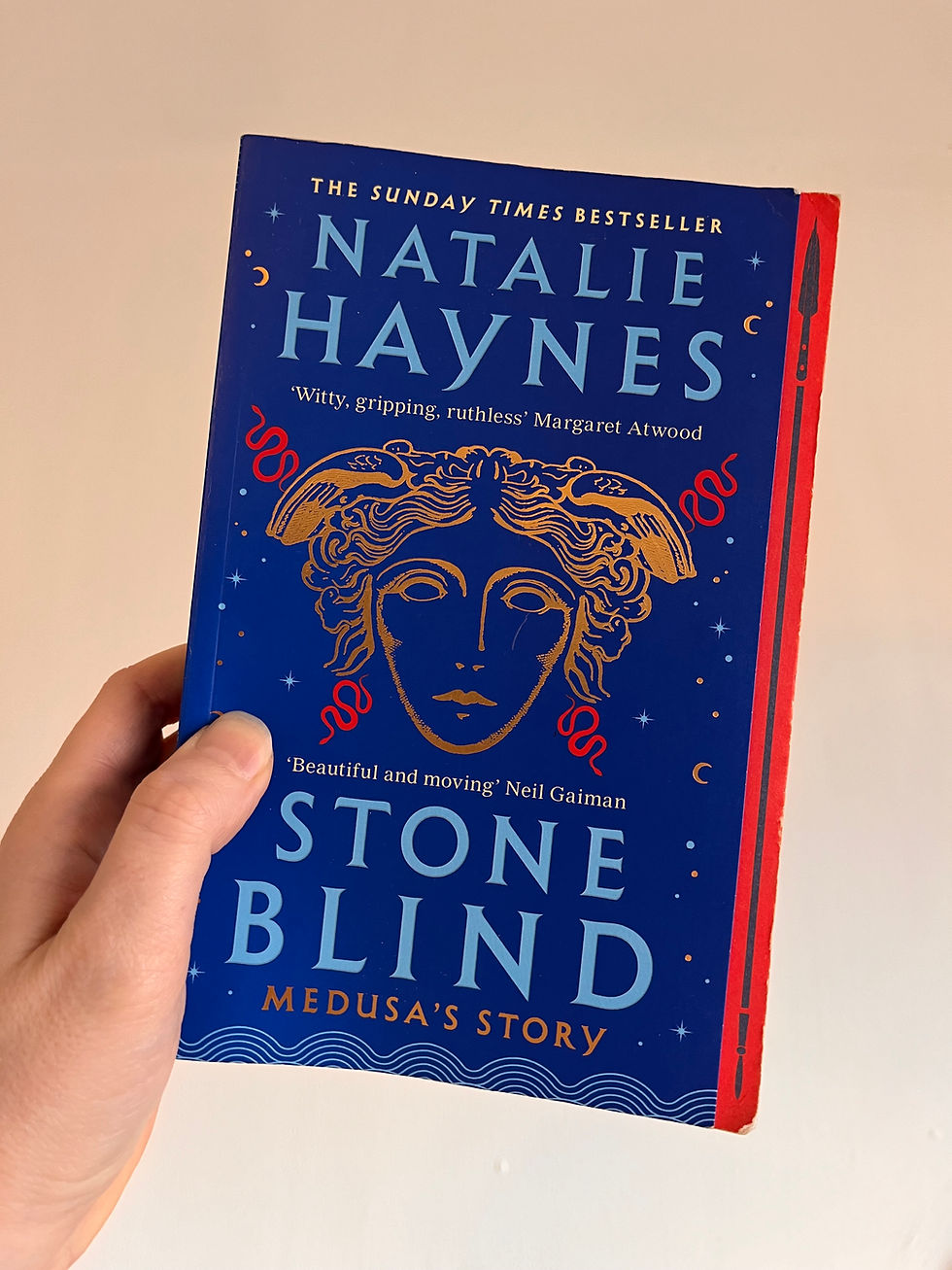

Stone Blind by Natalie Haynes

- theworldthroughbooks

- Jan 30, 2024

- 3 min read

Medusa is the sole mortal in a family of gods. Growing up with her Gorgon sisters, she begins to realise that she is the only one who experiences change, the only one who can be hurt.

When Poseidon commits an unforgiveable act against Medusa in the temple of Athene, the goddess takes her revenge where she can: on his victim. Medusa is changed forever – writhing snakes for hair, and her gaze now turns any living creature to stone. She can look at nothing without destroying it.

Desperate to protect her beloved sisters, Medusa condemns herself to a life of shadows. Until Perseus embarks upon a quest to fetch the head of a Gorgon…

Greek myths are becoming increasingly popular as literary retellings. What’s not to like? They are ready-made stories, filled with intrigue, drama, plots, revenge, love – you name it, there’s a Greek myth which covers it.

A sub-category of these retold Greek myths is that the perspective is shifted to the women. In recent years, historians have been pointing out that history is largely told by men and authors have been pointing out that folk tales and myths follow the same pattern. Women tend to be portrayed in these tales as either passive or evil – either as a character waiting to be rescued (I commented on subverting this assumption in my blog post about The Bloody Chamber), or as people who have cast unspeakable harm and need to be destroyed.

Medusa is typically cast into the latter camp. We all know her as a monster – an unsightly, malicious mad-woman, with snakes for hair and a deathly stare, seeking revenge on anyone who dares to visit her cave by turning them permanently into stone. Through the perspectives given in Stone Blind, Haynes challenges this perception and suggests that we only see Medusa in that way because her qualities starkly oppose those favoured in times gone by. We used to blindly accept that women should (and should want to) be beautiful, subservient and nurturing and Medusa’s appearance is the absolute antithesis of this, making her horrifying.

But no one has considered how Medusa herself felt about her inadvertent role in the events leading up to Perseus’ quest.

The fact that Medusa’s storyline is told with Medusa herself as the protagonist challenges the established perception of Medusa by portraying her initially as a quiet, curious girl, then as markedly subdued after the incident with Poseidon in Athene’s temple, and ultimately as someone who thinks of others before thinking of herself. Once she realises that Athene has caused her eyes to turn all living creatures to stone, she hides away in a cave, covering her eyes with bandages when she emerges, taking all possibly steps to prevent herself from inadvertently harming anything in the natural world, most importantly her sisters. This is a world away from the monster-Medusa we all know.

Perseus, on the other hand, is toned down. He is portrayed as impulsive rather than heroic, and Haynes highlights his failure to make a plan or to think of the consequences of his decisions.

Stone Blind is carefully structured. Normally the legend of Medusa is told as a standalone tale, missing the events leading up to her beheading and the events that followed for Perseus. Haynes begins various other storylines relevant to Medusa’s downfall and expertly weaves them together with Medusa at the centre.

Something I felt that Haynes did not address was the fact that Athene took revenge on Medusa as Poseidon’s victim, rather than on Poseidon himself. Obviously Haynes could not change the underlying plot – and of course Athene’s revenge is a crucial catalyst in it – but I wondered if Athene’s logic in attacking the female teenager rather than the adult male god could have been explained, even if it was just that Athene felt that it was her only option.

Haynes has an engaging writing style, particularly in the way she writes dialogue. It is fast-paced and realistic in that you do not have to suspend your disbelief very much in imagining how certain conversations would have gone. She varies the viewpoint of the narrative, at times writing to the reader from the first-person perspective and taking on the role of whatever objects are in the vicinity as an omnipresent observer. She also clearly knows her stuff, holding a degree in classics.

I have heard mixed reviews of Stone Blind but I personally thought it was well-crafted and well-told. I am certainly enjoying the trend of retelling these myths from the women’s perspectives.

Comments